Interventions V, Slum Upgrade Projects

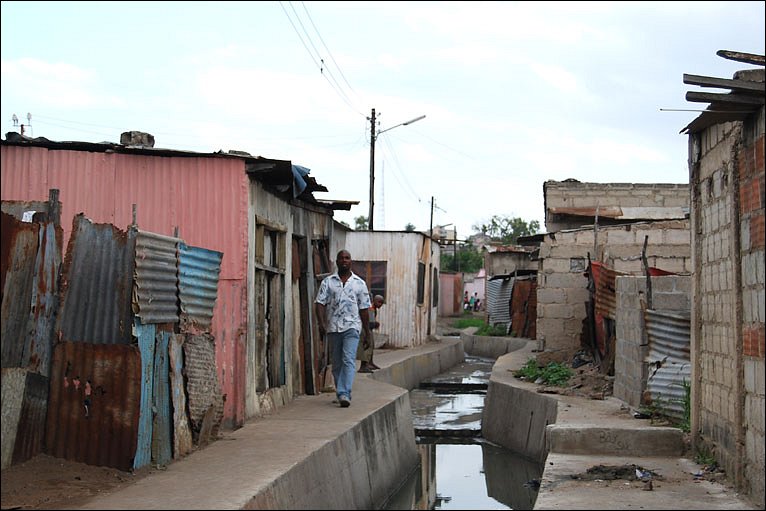

Drainage system in Mafalala, Maputo, 2016. Photo by Kate McGeown, BBC.

“Slum upgrading is a process through which informal areas are gradually improved, formalised and incorporated into the city. (…) The activities tend to include the provision of basic services such as housing, streets, footpaths, drainage, clean water, sanitation, and sewage disposal. (…) [However,] slum upgrading is not simply about water or drainage or housing. It is about putting into motion the economic, social, institutional and community activities that are needed to turn around downward trends in an area. In addition to basic services, one of the key elements of slum upgrading is bringing secure land tenure to residents as well as access to education and health care.” (Cities Alliance 2016)

The work of UN Habitat and the international system of aid organisations has for over three decades followed the paradigm that was first set in motion by the World Bank in the 1970s to upgrade slums rather than just clear and rehouse their populations. Coming on the back of Turner’s work on ideas of vernacular or traditional knowledge in building, of poor people’s creativity or of user sovereignty in self-housing solutions (Turner 1976), slum upgrade then evolved into a process usually tied to Structural Adjustment Programs, especially in African and South American cities.

The option for upgrading can be argued to be an imperative in developing countries, where the state has few resources for comprehensive options such as that of universal rehousing. However, slum upgrading can also be considered a neo-liberal policy in the sense that it aims to alleviate living conditions for slum dwellers without addressing the structural causes of poor informal housing. But since the alternative usually entails externally imposed clearance and relocation, slum upgrade is still regarded as a better solution for the communities involved:

“Local, national and international policies have steadily evolved from repressive approaches aiming to eradicate slums and control the ‘undesirable dwellers’ (migrants and other social ‘undesirables’) to an assimilating of the urban populations” (Bolay 2006: 285).

Effects on incumbent populations

One of the most debated consequences of slum upgrade projects is that they can often end up pushing the most vulnerable slum residents out of site. This is especially the case where the prevalent type of access to housing is made through informal rental systems. For instance in Nairobi, Gulyani and Talukdar (2008) note how the city’s slums constitute low-quality but high-cost shelter for the urban poor in the city, who see very little of the earnings from this informal housing economy re-invested to upgrade housing conditions. In such type of situations, “slum upgrade programs that create assets – such as housing with legal title – for slum residents that the better-off [also] lack are likely to be the subject of gentrification” (idem: 1921). In other words, once housing conditions or tenure are improved, home or deeds are quickly commodified and either grabbed by a slightly more affluent household or re-appropriated by the slum landlord class able to enforce evictions and passed on to those more affluent households.

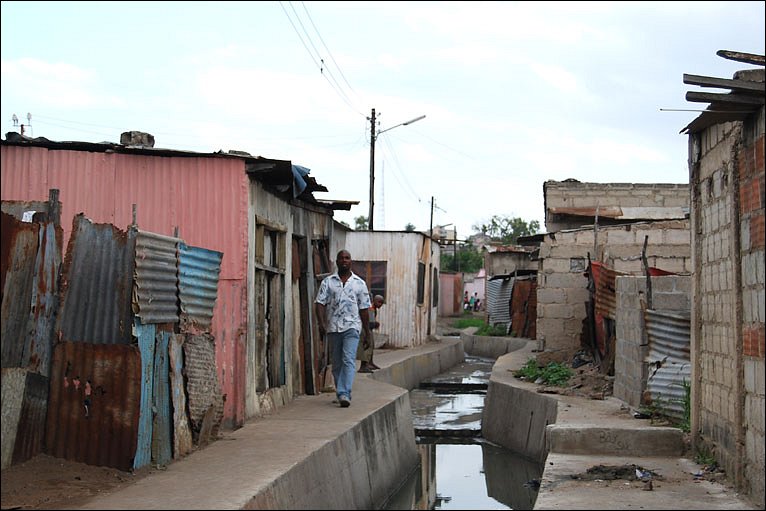

Drainage and other works (background) in Bairro Urbanização, Maputo. Photo by Ase Johanessen.

In the Portuguese-speaking landscape, comparable processes can be found in Maputo, Mozambique. There, slum upgrade projects conducted under the aegis of UN Habitat in informal areas near the city centre, such as Mafalala, Polana Caniço A or Maxaquene, have meant that those on the lowest incomes and tenure status security have been pushed further out, to areas such as Zimpeto or Magoanine B and C (Jorge and Melo, 2014). In Polana Caniço A (adjacent to the Sommerschield wealthy district), upgrade projects were immediately followed by the creation of a market to sell plots, which were informally transacted but sanctioned by municipal authorities. This means that those more vulnerable economically tend to sell and move away, substituted by lower middle-class individuals looking to build a detached, gated house. In addition, the PROMAPUTO plan in the area also meant the demolition of some of the settlement’s sections to make way for new roads, so the atmosphere among residents was that “the neighbourhood is not for us anymore” (idem: 65).

In short, slum upgrade projects (modelled after the UN-Habitat intervention paradigm or not) tend to be followed by the rapid increase of land and house values in the upgraded settlements, often resulting in the peripherization of significant sections of the target populations.

Advertisement for pre-paid electricity in Maputo, 2016. Image by Credelec.

Upgrade, entrepreneurship and the precarious subject

Such prevailing universes of displacement can nonetheless, as McFarlane (2012) as shown, be recast within broader urban entrepreneurialism agendas and become internalized as such by residents and activists. In such a situation, much-needed capital, symbolic and associational investment into activities to improve the lives of slum dwellers (such as collective toilet blocks, micro-finance projects and individual or collective squatter tenure) become framed within a particular “conception of poverty as socioeconomic potential and the poor as entrepreneurial subjects” (idem: 2796). Such projects’ overriding ideology aims to “transform spaces of poverty from an exploited proletariat to emerging markets that will be embraced by financially disciplined subjects” (idem: 2800), that is, slum dwellers themselves need to embrace these tenets in order to benefit from the projects. An instructive consequence is the way paid toilet blocks in informal settlements commodify personal hygiene to such an extreme (idem: 2804) that people’s bodily needs have to be relocated elsewhere, i.e. out to the open (Datta 2012: 130; Desai et al 2015).

Another is pre-paid electricity. The universal infrastructural ideal was not completed in Maputo and a pre-paid electricity system has been put in place in the last decade. Baptista (2016) shows that the working poor who rely on daily incomes and have had a history of incurring in debt they cannot serve when provided with 24/7 electricity have taken on pre-paid electricity meters provided by private companies. Uncertainty and provisionality guide everyday life. Against this backdrop, electricity meters have been key to shape a financially disciplined subjectivity among the poor, who like the divisibility of electric time it provides (knowing how much TV one can watch in the evenings with the earnings of the day and without incurring in debt) and have become technologically literate in operating the meter. But the question remains, to what extent is this sociotechnical progress, or simply adaptation to a precarious existence?

Many informal settlements across the world have become spaces of social experimentation for forms of governing the precarious lives of the urban poor, much like colonial cities were in the early 20th century. Desai and Loftus (2012) argue that at the core of the problem is the way infrastructure investments in slum areas have become conduits through which a ‘landlord class’ switches capital from a primary to a secondary circuit. Thus they prescribe a specific research agenda for the near future:

“Without a clearer understanding of the circulation of capital through land in slum areas there is a serious risk that benevolent investments in infrastructure will merely strengthen powerful stakeholders operating within and across slum areas, while increasing the already precarious nature of slum dwellers’ lives.” (idem: 790)

References

Baptista, I. (2015) ‘We Live on Estimates': Everyday Practices of Prepaid Electricity and the Urban Condition in Maputo, Mozambique, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39.5, 1004-1019.

Bolay, J. C. (2006) Slums and Urban Development: Questions on Society and Globalisation, European Journal of Development Research, 18/2, 284-298

Cities Alliance (2016) About slum upgrading. http://www.citiesalliance.org/About-slum-upgrading.

Datta, A. (2012) The Illegal City: Space, Law and Gender in a Delhi Squatter Settlement, Farnham, Ashgate.

Desai, V. and Loftus, A. (2013) Speculating on Slums: Infrastructural Fixes in Informal Housing in the Global South, Antipode, 45.4, 789–808.

Desai, R., McFarlane, C., and Graham, S. (2015) The politics of open defecation: informality, body, and infrastructure in Mumbai, Antipode, 47.1, 98-120.

Gulyani, S. and Talukdar, D. (2008) Slum Real Estate: The Low-Quality High-Price Puzzle in Nairobi’s Slum Rental Market and its Implications for Theory and Practice, World Development, 36, 10, 1916–1937.

Jorge, S. and Melo, V. (2014) Processos e Dinâmicas de Intervenção no Espaço Peri-urbano: O caso de Maputo [Intervention processes and dynamics in Peri-urban space: the case of Maputo], Cadernos de Estudos Africanos, 27, 55-77.

McFarlane, C. (2012) The Entrepreneurial Slum: Civil Society, Mobility and the Co-production of Urban Development, Urban Studies, 49.13, 2795–2816.

Turner, J.F.C. (1976) Housing by people, London, Marion Boyars.